One of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Most Controversial Quotes

Did Dietrich Bonhoeffer really say “abortion is murder,” or is there more to the story?

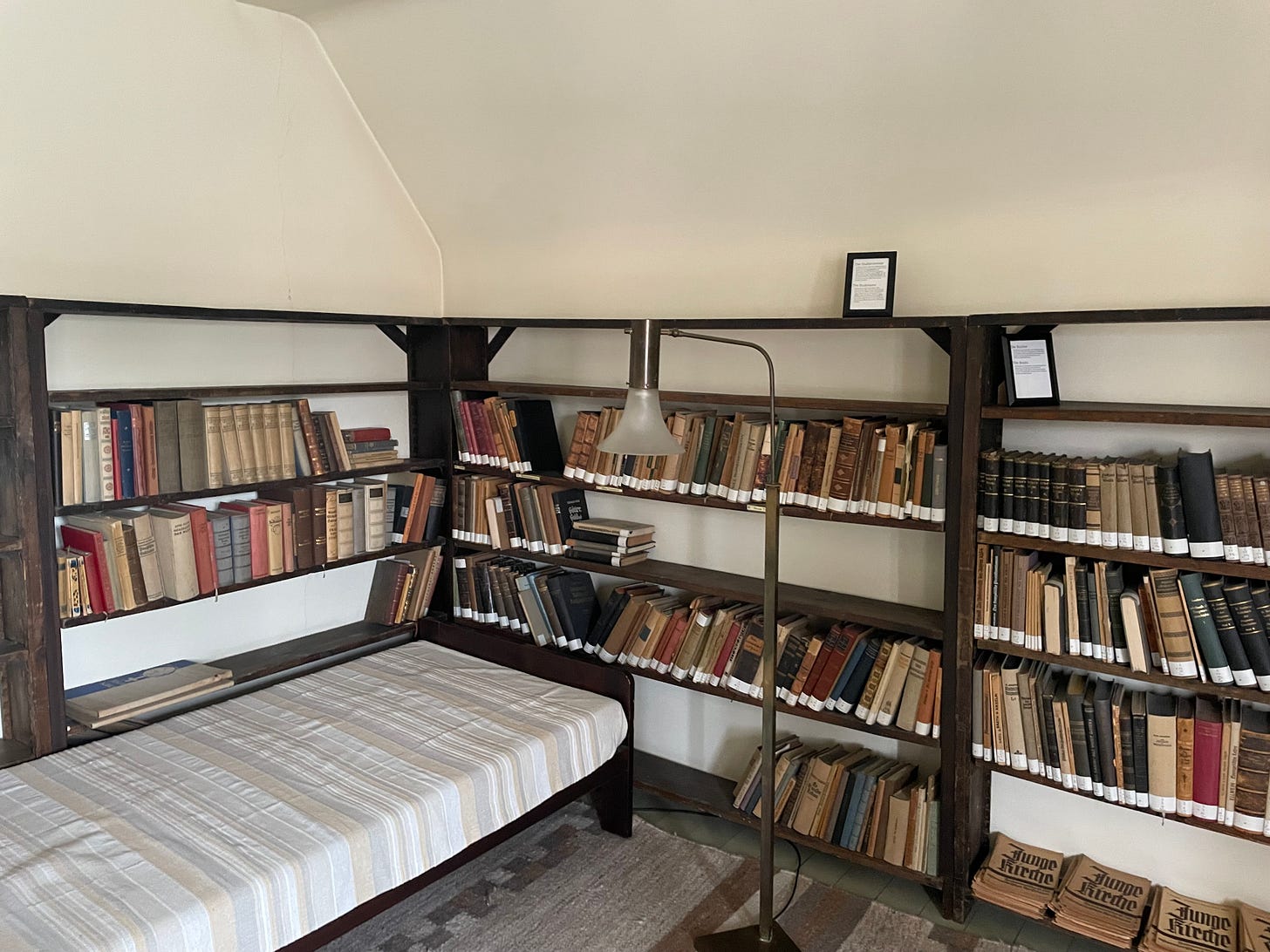

Photo: by Devin Maddox, Dietrich Bonhoeffer Haus, Charlottenburg, Berlin

Bonhoeffer, in Ethics, wrote, “The natural must be recovered from the gospel itself.”[1] This simple statement is tacit rejection of all other sources of authority. The gospel itself must be the final arbiter in the debate over what is natural. Bonhoeffer, in this simple quote, repents of the volkish religion of the Nazis, which leaned upon modernism’s most radical expression—nihilism.

Jean Bethke Elshtain explains:

"It is hard to overstate the importance of naturalness and embodiment for Bonhoeffer. He saw around him arguments that demeaned or diminished embodied integrity and came to fruition in evil practices. The first step down this road was the failure to find value in life itself. That, in turn, permitted the Nazi state to construct itself as the final horizon of meaning.[2]

The final horizon of meaning of the Nazi state was bathed in nihilism. The state itself was the very embodiment of nihilism—not exactly what Martin Luther had in mind, though that is precisely what the Nazis claimed from their pulpits. The Nazis deemed themselves judge, jury, and executioners—the final horizon of meaning could be found at the gallows, gas chambers, and firing lines in camps across central Europe. The antidote to nihilism, the gospel, would have to be stewarded underground by the Confessing Church.

Bonhoeffer wrote to his friend Eberhard Bethge, a fellow leader in the Confessing Church movement, shortly before his execution:

“What keeps gnawing at me is the question, what is Christianity, or who is Christ actually for us today? The age when we could tell people that with words—whether with theological or with pious words—is past, as is the age of inwardness and of conscience, and that means the age of religion altogether. We are approaching a completely religionless age; people as they are now simply cannot be religious anymore. Even those who honestly describe themselves as ‘religious’ aren’t really practicing that at all; they presumably mean something quite different by ‘religious.’ But our entire nineteen hundred years of Christian preaching and theology are built on the ‘religious a priori’ in human beings.”[3]

In a “world come of age,” in a world wrecked by a nihilistic definition of what is natural and unnatural, Bonhoeffer believed that the rug had been pulled out from under the church, obliterating the “religious a priori” in the culture. The gospel, therefore, would have to stand on its own, without the inertia of a religious culture behind it. Just as it has in America, the Bible-Belt of Germany—to torture a metaphor—would give way to the “Rise of Nones” among the German people after the war.

The collapse of religious infrastructure in the culture provided greater moral clarity on otherwise complex issues. As cultural incentives for biblical positions in defense of human dignity for all people diminished, far greater was the need for greater theological precision. The Confessing Church would have to invent a new religious language and teach the German churches their new language, simultaneously. German Christians who resisted the Nazis had everything to lose—including their lives. Bonhoeffer serves as an example of a man who staked his life on the belief that the gospel alone should define what is natural, and what is unnatural.

In Ethics, Bonhoeffer’s framework for natural moral law begins with the sacredness of human life. Bonhoeffer laments that, since Protestant ethics had drifted under the supervision of the German Academy during his lifetime, Catholic moral teaching was the only tradition that maintained a workable biblical position that rooted the sacredness of human life in the natural moral order.[4] Bonhoeffer writes, “Since all rights are extinguished as death, the preservation of bodily life is the very foundation of all natural rights and is therefore endowed with special importance.”[5] Murder, therefore is a violation of God’s will to endow humanity with natural rights. For Bonhoeffer, abortion qualified as murder.

Bonhoeffer writes:

"To kill the fruit in the mother’s womb is to injure the right to life that God has bestowed on the developing life. Discussion of the question whether a human being is already present confuses the simple fact that, in any case, God wills to create a human being and that the life of this developing human being has been deliberately taken. And this is nothing but murder.”[6]

Bonhoeffer’s words are strong, whether rendered in English, or the original German. They would not poll well during a presidential election in America. But Bonhoeffer did not mince words about what he believed abortion was. At the heart of it, abortion is the most unnatural act a mother can perform, because the most natural thing for a mother to do, Bonhoeffer argued, is to bring forth life entrusted to her by God.[7] The act of killing one’s own offspring is in direct conflict with the very foundation of the natural moral order. When a culture normalizes extinguishing human life, the entire natural moral order collapses under its weight.

Bonhoeffer’s words on abortion are clear, and pro-life Americans who might consider Bonhoeffer as “one of them” own might nod smugly in unison upon reading his Ethics. But Bonhoeffer scholar Clifford J. Green warns that Bonhoeffer’s writings on abortion should not be extrapolated into partisan government policies. Green warns that Bonhoeffer’s ideas are not abstract—what he seems to suggest, specifically, is that Bonhoeffer’s ideas are not culturally transferrable—and his implication seems to be that they should not be used in support of American pro-life political policies. Green speaks here for himself in “The General Editor’s Introduction” to Ethics :

"Here discussions about euthanasia, marriage, contraception, abortion, sterilization, and suicide are not abstract but highly contextual…Understanding this context leads to caution about how these views should be deployed in quite different situations many decades later… The abortion issue presents a similar dilemma. In Nazi Germany abortion was illegal, but the Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases was amended in 1936 to make compulsory the abortion of ‘genetically unfit’ fetuses up to six months in utero. Such Nazi “genetic engineering” is clearly in Bonhoeffer’s sights: ‘this is nothing but murder.’ To be sure, that is not the only circumstance and motive he addresses in his one brief paragraph on abortion. It is very problematic, however, to extrapolate from that context a general principle on abortion that would apply to quite different cases and contexts. Making such an extrapolation the justification for state legislation is doubly problematic since in this manuscript Bonhoeffer defends the rights of the individual against state intrusion.”

One familiar with the public discourse on abortion policy in the United States can see where Green is coming from. When a modern American writer says, “Abortion is murder,” it is most likely to be read in partisan, judgmental, unsympathetic, and un-nuanced tones. The fault lines between pro-life and pro-choice advocates open a well-worn polemical chasm, and opponents retreat to their corners. “What about the case of rape? What about incest? What about cases to save the life of the mother?” These are complex, serious situations. And a partisan debate on the issue that calls on Bonhoeffer for support would be flagged by Green as poor form.

One such example, according to Green, would be the popular writer Eric Metaxas’ biography on Bonhoeffer. In an interview with the Catholic News Agency to promote his book, Metaxas wrote, “on abortion and euthanasia and stem-cell research. . . . We would do well to take our lead from [Bonhoeffer] in our own battle on that front.” In response (in a scathing, now famous, book review), Green blithely retorted, “Given all this, the most descriptive and honest title for Metaxas's book would perhaps be Bonhoeffer Co-opted. Or better: Bonhoeffer Hijacked.”[8] Metaxas’ comments were evidently read as a partisan cooption of Bonhoeffer’s ideas about abortion. They were read the way an American pro-choice voter would like read Bonhoeffer.

Though Green may write off Metaxas as out of league with those in his International Bonhoeffer Society (Green has been the leader of the group for decades, and presumed the premier English-speaking Bonhoeffer scholar), he would find it far more difficult to write off former University of Chicago scholar Jean Bethke Elshtain. Elshtain took up the very same question as Metaxas: “What would Bonhoeffer make of America’s embrace of so-called ‘reproductive-rights?” In regards to our impulse toward the unlimited "right" to abortion, Elshtain writes, “Bonhoeffer, were he alive to assess all this, would be a powerful critic of the distorted notions of human freedom being enacted among us today.”[9]

I would concede, in agreement with Green, that we are in dangerous territory when we presume to be “omniscient narrators” on behalf of historical figures. We cannot read Bonhoeffer’s mind. But this is not one of those times.

Bonhoeffer’s ideas regarding about abortion are not veiled in secrecy; they are clear because they are recorded in Ethics. And they are not without nuance! Bonhoeffer continued his thoughts in Ethics signaling sensitivity to the complexity of the abortion issue. Here, Bonhoeffer describes the torment of those that face the decision to terminate the life of their unborn baby:

“Various motives may lead to such an act. It may be a deed of despair from the depths of human desolation or financial need, in which case guilt falls often more on the community than on the individual. It may be that on this very point money can cover over a great deal of careless behavior, whereas among the poor even the deed done with great reluctance comes more easily to light. Without doubt, all this decisively affects one’s personal, pastoral attitude toward the person concerned; but it cannot change the fact of murder. The mother, for whom this decision would be desperately hard because it goes against her own nature, would certainly be the last to deny the weight of guilt.”[10]

Here, Bonhoeffer acknowledges the systematic economic drivers of abortion rates. Bonhoeffer laments those socially complicit when lives are discarded because mothers feel trapped in a world without hope. It would not take much an imaginative leap to venture a guess as to how Bonhoeffer might read the racial correlations between the abortion rate in urban centers and cycles of poverty among minority communities (Bonhoeffer predicted racism in America as “the problem” that would plague America’s future).[11] Bonhoeffer even sympathizes with the mother, in a moment of profound solidarity, in her agony when she decides to abort her baby. But, with tremendous empathy, Bonhoeffer is yet unwavering. The fact remains, like it or not, for Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “abortion is murder.”

[1] Ethics, 173. Emphasis mine.

[2] Jean Bethke Elshtain, Bonhoeffer On Modernity: “Sic et Non,” The Journal of Religious Ethics, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Fall, 2001) pp. 345-366.

[3] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters and Papers from Prison (ed. Clifford J. Green; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1998). 362-363.

[4] Ethics, 172.

[5] Ibid. 185.

[6] Ibid. 206.

[7] Ibid. 204.

[8] Clifford Green, "Hijacking Bonhoeffer," Christian Century (Oct. 5, 2010), at www.christiancentury.org/reviews/2010-09/hijacking-bonhoeffer,accessed Jan. 13, 2011.

[9] Jean Bethke Elshtain, Bonhoeffer On Modernity: “Sic et Non,” The Journal of Religious Ethics, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Fall, 2001) pp. 345-366.

[10] Ethics, 206-207.

[11] Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Barcelona, Berlin, New York: 1928 - 1931. Clifford J. Green ed. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2008. 314 ff.

Outstanding work here, Devin. Love it.

Thanks for presenting thoughtful scholarship and insight without defensive insecurity. You wonderfully revealed Bonhoeffer’s conviction while alerting us to his constant awareness of the messiness of life in this fallen world. Keep writing !!